This post is part of a series. Use the links below to navigate between posts.

| ⬅️ Previous Post | ⬆️ Series | Next Post ➡️ |

|---|---|---|

| No previous post. | Embedding-Based Steam Search | Part 1: Obtaining Data |

This post contains definitions, background information, and a broad overview of how the Steam Game Search project works. Feel free to skip any sections that you’re already familiar with.

Overview

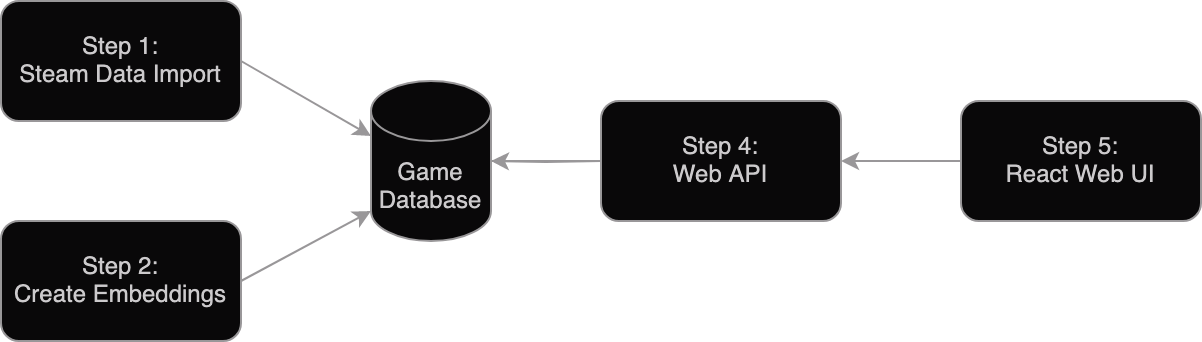

The project was broken down into multiple steps, each of which is covered in its own post. A brief summary of each step is below. Each piece was implemented with Python.

To create embeddings, first you need some data. This post covers obtaining the data from Steam’s API, storing it in a database, and issues that arose along the way.

This post covers how to use Instructor to create embeddings, and how to store them in a database that doesn’t natively support them (sqlite3).

(Not pictured in the diagram above)

This post covers the math involved in querying the database for similar embeddings, and how to use that to create a simple search engine.

This post covers how to create a simple API using Flask that can be used to query the database, and how to deploy it using Docker.

The final post covers how to create a simple webapp using React that can be used to query the API and display the results in a user-friendly way.

Background Information and Definitions

In order to understand how the project works, it may be helpful to understand some basic concepts about how machine learning models work, and how they process text. This section will cover some of the basics.

Tokens and tokenization

Machine learning models don’t look at text the same way we do, they don’t see individual letters. Instead, words are broken down into short sequences of characters and assigned a numeric value from 0 up to the specific model’s “dictionary size”. These numbers are called “tokens”.

There are also special tokens that represent things like the end of a sequence or padding (a placeholder value that is used to make all input sequences the same length when batching multiple sequences together into a single call to the model).

As a hypothetical example, you might break down the string “Hello, how are you?” into the 7 tokens [Hello, ,, <space>how, <space>are, <space>you, ?, <end_of_sequence>].

A vague rule of thumb is that one token is about equivalent to 4 characters of text.

These tokens are what the model sees as input, and in the case of LLMs (Large Language Models, such as ChatGPT), they are also what the model predicts as output. What we’re interested in, however, is something else. When we feed a piece of text into a model, we want to get back a bundle of numbers that represents that text. This is called an “embedding”.

Embeddings

See also: OpenAI Embeddings Guide for a quick overview of embeddings and their uses.

Implementation-wise, an embedding is just an array of numbers (usually floating point values). As a whole, those numbers represent an individual piece of text. You can then use math on them to accomplish a variety of things. The most common use case is to figure out how similar two pieces of text are to each other. But you can also do other things with these embeddings, as I’ll show later.

By using similarity, you can do things like find the most similar games to another game based on their user reviews, or discovering a game that best matches a given description of game play and mechanics.

A common way of generating embeddings is to use an LLM which would normally predict the next token in a sequence, but instead cut the model short and just before the model outputs its prediction, read the internal state of the model. This internal state becomes the embedding. So even though embeddings aren’t necessarily related to LLMs, as of now LLMs are the best way we have of generating them.

For this reason, it should be pretty obvious that embeddings from one model are generally not ’transferrable’ to another model, which also means that embeddings cannot be compared across models.

Instructor

Instructor is a text embedding model that can be used to generate embeddings for text. How it works is out of scope for this series of articles, so we’ll be treating it more or less as a black box that takes in text and spits out embeddings.

As far as using it goes…

As input, Instructor takes in a max sequence length of 512 tokens (< 2000 characters), which means that it can’t encode anything longer than that into a single embedding. If you want to encode something longer than 512 tokens you need to break it up into smaller pieces and encode each piece separately. This process is called “chunking” and can have a significant impact on the quality of the embeddings depending on how it’s implemented.

For output, Instructor returns a 768-dimensional embedding for each input sequence. This means that the array representing the embedding will be 768 elements long, or about 6KB in size (768 * 8 bytes per float = 6144 bytes in the case of 64-bit floats).

There are two ‘sizes’ of Instructor. instructor-large and instructor-xl, with this project using the latter. The size of the model determines how many parameters the model contains, which affect the quality of the embeddings and how long (how many operations) it takes to generate them. A bigger model generally produces better, more accurate embeddings. The drawback is that larger models take longer to train, longer to generate embeddings, and require more memory to run.

Just as a note, the size of the model does not necessarily affect the size of the embeddings themselves. The size of the embeddings is determined by the model architecture, or how the model was designed. In the case of Instructor, both large and xl versions produce 768-dimensional embeddings.

Additional Reading

These are links to some additional resources that I found useful while trying to wrap my head around text-based machine learning models.

- What Is ChatGPT Doing … and Why Does It Work? - A thorough article by Stephen Wolfram explaining in detail how LLMs like ChatGPT work.

- LLM Visualization - A visualization tool and explanation by Brendan Bycroft that breaks down step-by-step the internal mathematics that LLMs are performing.

| ⬅️ Previous Post | ⬆️ Series | Next Post ➡️ |

|---|---|---|

| No previous post. | Embedding-Based Steam Search | Part 1: Obtaining Data |